In the past two years, everyone has been discussing new forms of software interaction empowered by AI capabilities. The industry refers to the traditional software interaction method as GUI, while the interaction method for native AI applications is summarized as CUI (Conversational User Interface). This is an oversimplification. The concept of CUI easily leads people to associate it with chatting with AI. The idea is to interact with the system through a chat interface to achieve the desired outcome.

Goodbye to the cumbersome GUI, and now the user only needs to focus on a chat box and talk to get things done. This sounds desirable, but it’s mostly unrealistic fantasy.

Some continue to modify CUI by adding information interaction cards within the conversation. These cards can contain parts of the information from the GUI, such as a data chart, or include a set of buttons for users to select an appropriate subsequent action. This approach is an improvement, but the idea of incorporating the entire software usage process into one conversation thread remains unrealistic. It’s not even a reasonable interaction method.

User interaction is always highly contextual.

First of all, users don’t always start using software from a blank slate. More often, they start with existed objects. For example, when using AI-powered Photoshop to edit an image, it’s often about processing a specific area of the photo. For instance, “remove the bag that the woman is holding in her left hand.” At this point, using CUI interaction is very foolish because the woman may have two bags in her hands — how would the AI know which one to remove? Therefore, Photoshop users still use the mouse to click and activate AI features.

The same goes for enterprise software. Whether it’s the sales process based on customer records or the processing flow based on workpieces and materials, users always need to select actions based on data records. Users inevitably need to use a visual method to locate the specific record. Once the context is established, AI processing accuracy improves, and users gain more confidence in their actions.

In fact, early generative AI applications in text processing and note-taking software worked similarly. Users would directly select a piece of text in the original editor and then apply AI functions like “expand” or “summarize.” This interaction is clearly closer to the traditional GUI.

User interaction requires visual assistance and guidance.

In a manufacturing execution software, when starting a new work process, it’s necessary to obtain the identification ID from physical materials, often through optical scanning or RFID recognition. After identifying the workpiece, relevant process and SOP (Standard Operating Procedures) need to be displayed. These pieces of information cannot be effectively handled by CUI; they may include a detailed checklist, three processing diagrams, and several well-laid-out buttons. Throughout the entire processing stage, this visual interaction must always be present. The user ultimately clicks the “complete” button in the process checklist to quickly confirm and switch between SOPs and diagrams. Although this is a traditional interaction, it is the most effective. AI intelligence and CUI do not have value for such tasks.

Some may challenge this process as a transitional phase. With more intelligent AI in the future, we might fully automate processes from customer orders to procurement, production, and delivery. This would eliminate the need for manufacturing management software because AI would quietly take care of all the details. However, this is simply not possible. Our world is not driven solely by software but also constrained by numerous physical conditions. Even if all physical controls are automated, we still have to deal with procurement negotiations between upstream and downstream, and even trade barriers between countries. An application software company cannot afford to pause and wait for world unity. Therefore, our reasoning must be based on a gradual path. To put it simply, we are designing the product form for 2025, not preparing for 2030 or 2075.

User interaction requires safety confirmation.

User interaction is not just about executing input and waiting for output; it also involves carefully checking the effectiveness of the output. For example, when a retailer uses a QR code to collect payment, hearing “$100 has been deposited into your account” is a reliable output. It uses very simple TTS (Text-to-Speech) technology, but it’s extremely effective.

Many software interaction output reviews are much more complex. When a user has set up a process node in workflow software, they can use a configuration window to check whether each parameter meets their expectations. Even simple home automation requires confirmation: when I’m 100 meters away from home, should the air conditioning turn on? What temperature should it be set to? Should all lights be turned on, or just the porch light? This might be simple, and a conversation could potentially cover it. But in enterprise process automation, the actions involved are much more complex than turning on lights or air conditioning. If AI generates these processes, the results must be presented in a specialized visual form. This inevitably returns us to the GUI model. Existing software products already have frontend interfaces that need enhancement, but they cannot be completely bypassed by AI. They still need to present each process parameter in detail.

In critical areas of enterprise software, even if the intelligent system can handle very complex tasks, users are reluctant to trust it completely. To establish this trust, the only way is to display the intermediate processes to users. This display process relies heavily on traditional GUI.

User interaction is a gradual creative process.

In the field of no-code application platforms, a company launched a “one-click generate application” feature two years ago. For example, “Generate an ERP system for the garment manufacturing industry.” Not only was this functionality useless two years ago, but it still is today.

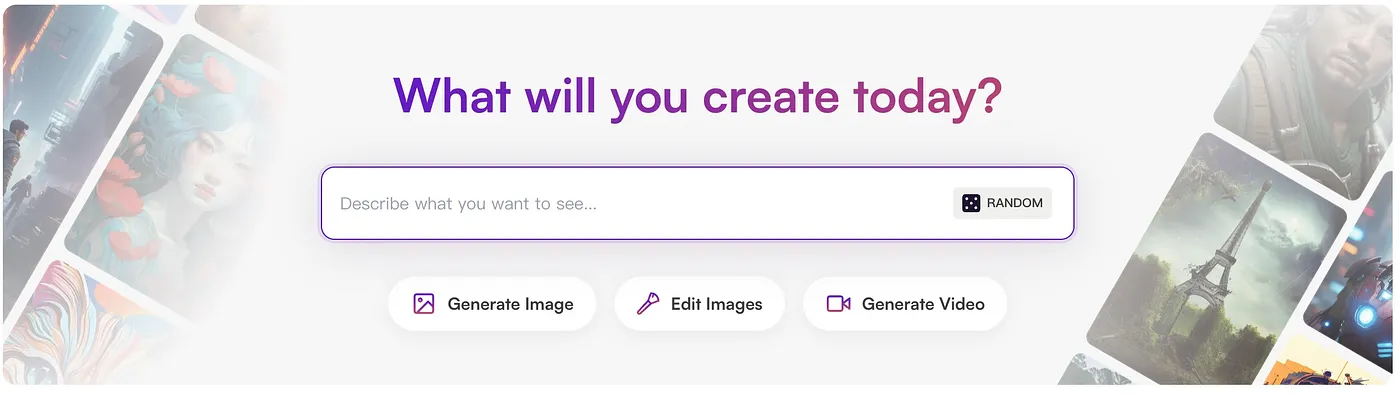

Would enriching the prompt solve the problem? Perhaps we can first write a detailed requirement document? No, this won’t work either. This is because human creation of all information products is a gradual unfolding process. Developing an application is like this, writing an article, painting a picture, or composing a piece of music — all rely on iterative refinement, weighing, and making balanced choices. Spontaneous creation, producing a perfect piece of work in a snap, is a legend, not the norm. Therefore, when it comes to using AI to complete tasks, we rarely use a single prompt to instruct the AI to complete the whole task. Just like with text-to-image applications, they need to provide multiple pieces of artwork for the user to choose from, and allow the user to further refine the selection through prompts.

Thus, we face the challenge of how to get users to confirm intermediate results. These intermediate results still require a specific GUI for expression. In professional music composition AI applications, the generated results are not just WAV audio files but need to be presented on sheet music. This relies not only on industry standards like Music XML but also on professional software architectures that allow users to adjust notes and symbols. In this case, we find that native AI applications strongly resist reverting to the old GUI approach. After researching several popular generative AI music applications, none of them provide an editing capability based on sheet music. They only allow users to modify segments of a song through prompts. While these products allow users to regenerate parts of the song (Refill), they don’t offer precise control capabilities. On the other hand, established music notation software still lacks generative AI capabilities.

This phenomenon is the divide that has emerged in the software industry with the advent of generative AI. Native AI believes that there is no longer a need for existing legacy software, while traditional software watches nervously as AI capabilities progress rapidly. I believe this suspense is about to end because a new paradigm that is being gradually validated is taking shape. This paradigm will fully integrate generative AI capabilities while also providing a clear direction for modifying existing software applications. This will be a hybrid paradigm, driving industry segmentation, and bringing market efficiency. I summarize this paradigm with five verbs, calling it the IVERS paradigm (Instruct, Visualize, Edit, Re-instruct, Submit).

Next, I will explain this model in detail. After reading it, you will not find it unfamiliar. More and more applications are starting to adopt this model, such as GitHub Copilot and Cursur in the AI programming field, and Zapier in the workflow field. Although these successful examples come from different backgrounds, they are gradually building a clearer paradigm that connects AI capabilities with traditional GUI. This paradigm leverages human-machine collaboration to improve efficiency while ensuring human control for accuracy.

Can traditional software and generative AI capabilities converge? The answer is definitely yes. However, traditional software, as a precursor technology before the advent of generative AI, also needs to reach necessary technical milestones. Just like before mechanical power appeared, the horse-drawn carriage needed to design key components like the axle and the carriage frame. Once mechanical power were modularized, only the power source needed to be replaced. Of course, the actual process is far more complicated than just the principle. There was a gap of over twenty years between the early internal combustion engine and the first car.

Today, traditional software vendors are actively seeking effective ways to integrate AI capabilities into their architectures. This model must achieve several necessary goals:

- Help users accelerate task completion while maintaining accuracy.

- Ensure that iterations and transformations in generative AI technology do not disrupt the continuity of application products.

- Maintain existing product differentiation advantages.

A metaphor of the horse-drawn carriage with the internal combustion engine is as follows:

- The carriage must continue to move safely and faster.

- The upgraded internal combustion engine must still be able to fit into the existing carriage.

- Whether it’s a luxury carriage or a cargo carriage, both must be able to utilize the internal combustion engine’s speed.

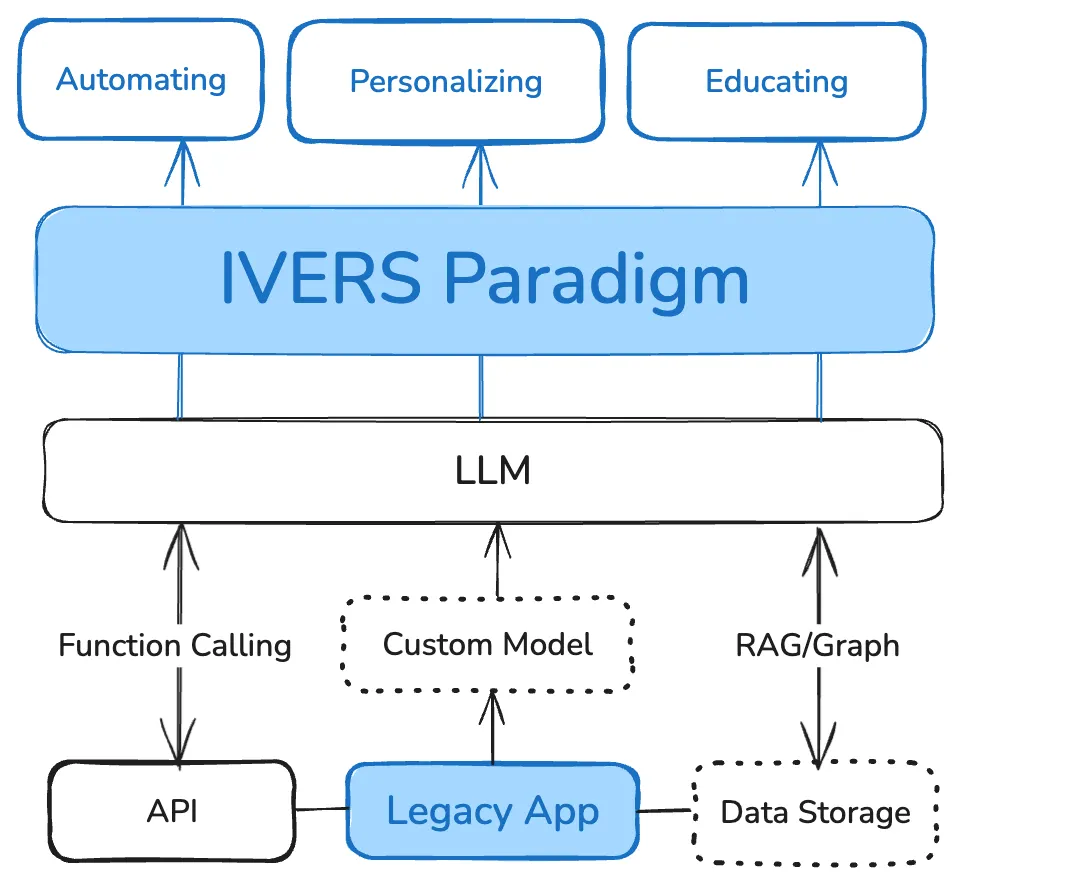

To achieve this vision, the software industry has already explored some feasible paths in the past one or two years and has begun to assemble a more stable framework. The diagram below is an abstract summary of this framework.

To leverage the power of LLMs, application software has three main ways to utilize them:

- Custom Models: This includes fine-tuning open-source models and public large models. Fine-tuning improves accuracy in specific domains like healthcare, law, and finance. Software vendors in these vertical fields widely use this path to create more usable products.

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) and GraphRAG with knowledge graphs. This path is commonly used in enterprise customer service, knowledge base retrieval, and question-answering fields to provide large models with coverage over private enterprise data.

- Function Calling: This is the most important way to integrate traditional software with generative AI capabilities. Application can define functions (APIs) for its own data sets and events. The AI then analyzes the semantics of the instructions, converts them into precise calls and parameters for the application, and the software return the response, which is then passed back to the AI. Through function calling, generative AI can establish interoperability with applications.

At the bottom of the diagram, these three technical paths are outlined. There is now a consensus in the industry on this. Especially with function calling, almost all AI applications must incorporate this capability. Even ChatGPT itself relies heavily on this feature to serve end-user scenarios. However, at the top of the diagram, where the integration between large models and traditional software user experiences is depicted, there are still divergences.

Before this, some applications adopted the Copilot concept, using an assistant to activate AI capabilities and interact with the system via chat. interface. i.e, starting a product journey through a chat window.

After completing the generation task, users can continue chatting with AI to modify the generated content. At this point, the user experience begins to decline. Users feel that no matter how they prompt, they can’t get precise control over the results. In image, music, and text generation, users commonly experience this. This problem also exists in use cases like code and application generation. Even Cursur can’t guarantee that a set of prompts will generate fully accurate and comprehensive code. Fortunately, Cursur is developed based on VS Code, which is a fully-featured integrated development environment (IDE), allowing developers to freely manipulate projects and files. However, native AI applications don’t have this “precursor technology.” Apart from text generation, they can only generate outputs; they cannot generate with the option to edit later.

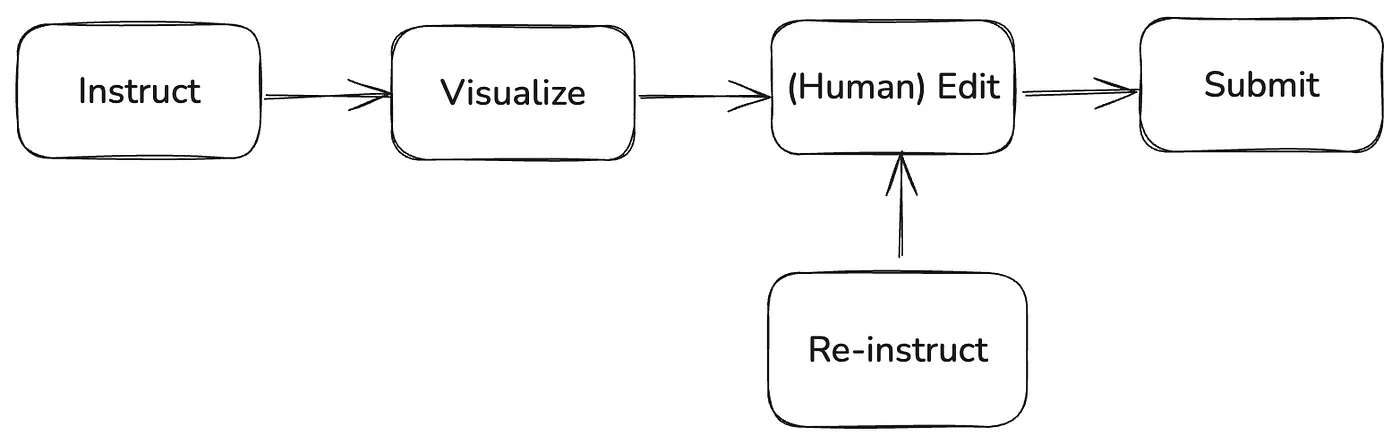

For serious business and professional applications, this is clearly insufficient. Especially for enterprise applications, users rely on them to complete very complex and critical tasks. All data or application fragments generated by generative AI must undergo user confirmation. This confirmation process must be properly presented through a GUI. This is why we need to incorporate a new paradigm into the fusion framework between AI and software products. I call this paradigm IVERS, which stands for Instruct, Visualize, Edit, Re-instruct, and Submit. The user gives instructions (which can also be triggered automatically); the software provides a visual rendering with operational handles; if the user is dissatisfied, they can issue new instructions or make manual edits; and finally, after confirmation, the process is submitted. Through this paradigm, we can connect the power of generative AI with the interaction tracks laid by existing software tools. This is like attaching a horse-drawn carriage axle to a mechanical power transmission device.

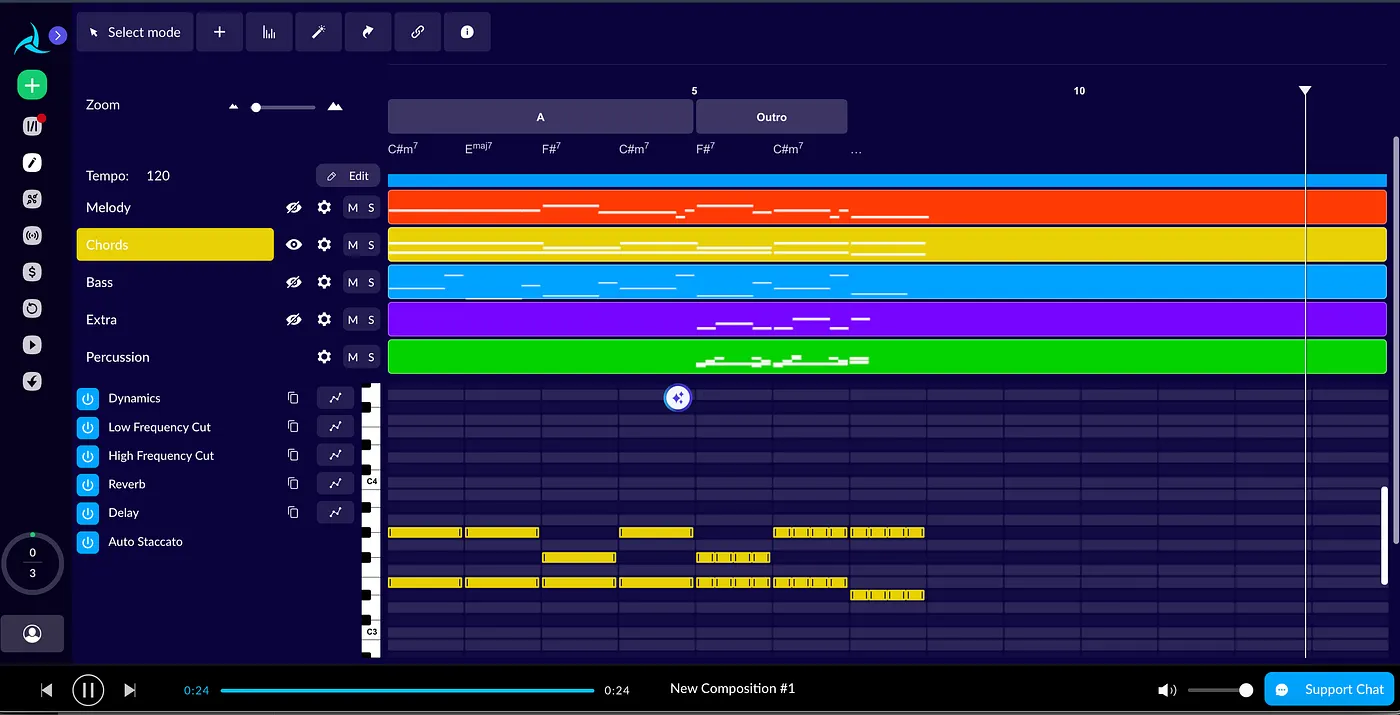

To understand this paradigm, let’s look at a simple example first. This application is called AIVA, an AI music composition tool born before the generative AI era. Unlike native AI applications, this product focuses on providing AI assistance for professional composers. The AI does not generate audio files but generates a structurally precise music file. This file can be opened with a proprietary editor, giving users full control over elements like rhythm, notes, and tracks. These controls for presenting the music elements all have handles that allow user manipulation. Users still rely on GUI for interaction.’

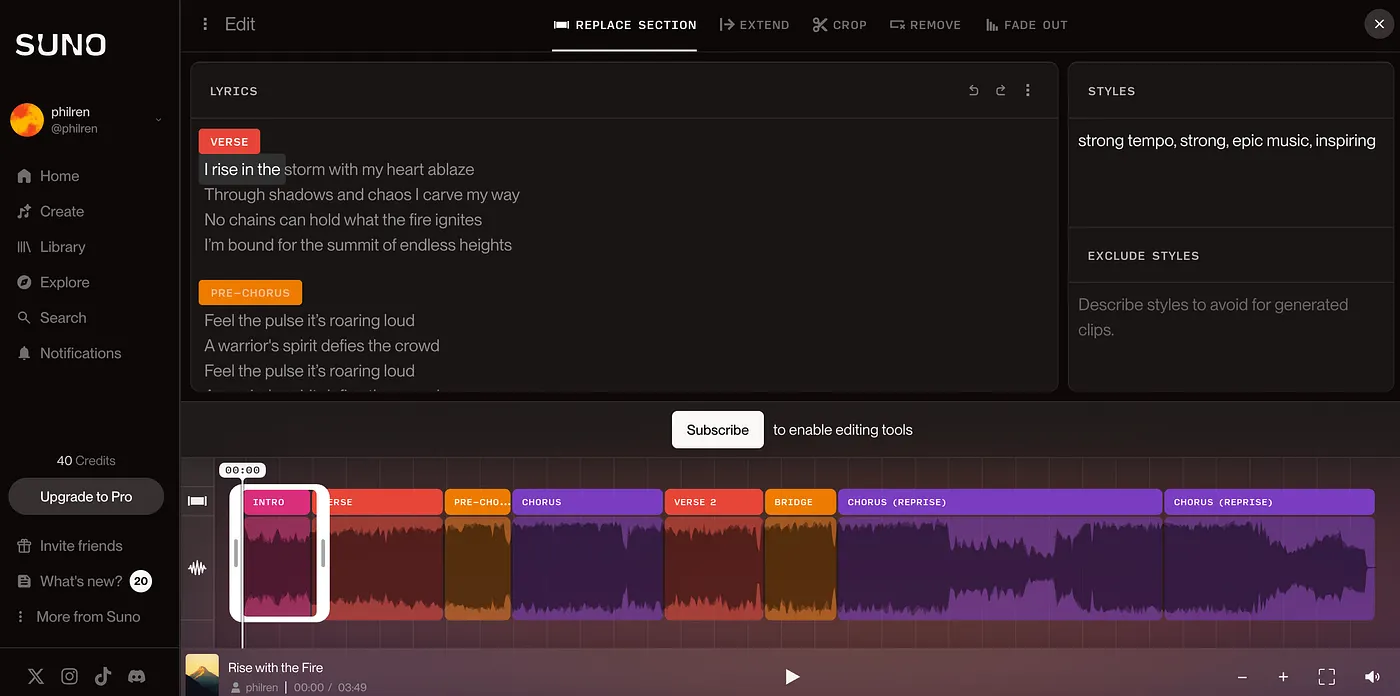

In contrast, newer native AI applications like SUNO generate music files based on prompts, but they only provide a Song Editor for users to modify segments of the song using new prompts. Ultimately, this approach generates music as it is, and users can’t have precise control over the results.

In the first example, AIVA follows the IVERS paradigm, while SUNO follows the CUI approach. In the music composition field, SUNO may still meet the needs of non-professional creators at an amateur level. However, in the enterprise software field, there are no amateur needs. Every software must be capable of precisely completing user tasks. This is why most traditional software adopts the IVERS paradigm, allowing users to accurately edit and submit.

This mechanism does not imply backwardness. In industries and enterprises, due to division of labor and responsibility, every computation task is often divided into stages completed by different roles. Sometimes, this is not due to lack of technical capabilities but because of social and legal requirements. Even if AI one day accurately diagnoses diseases, it can only prescribe a suggested prescription, not directly produce a pill in a blind box to be given to a patient.

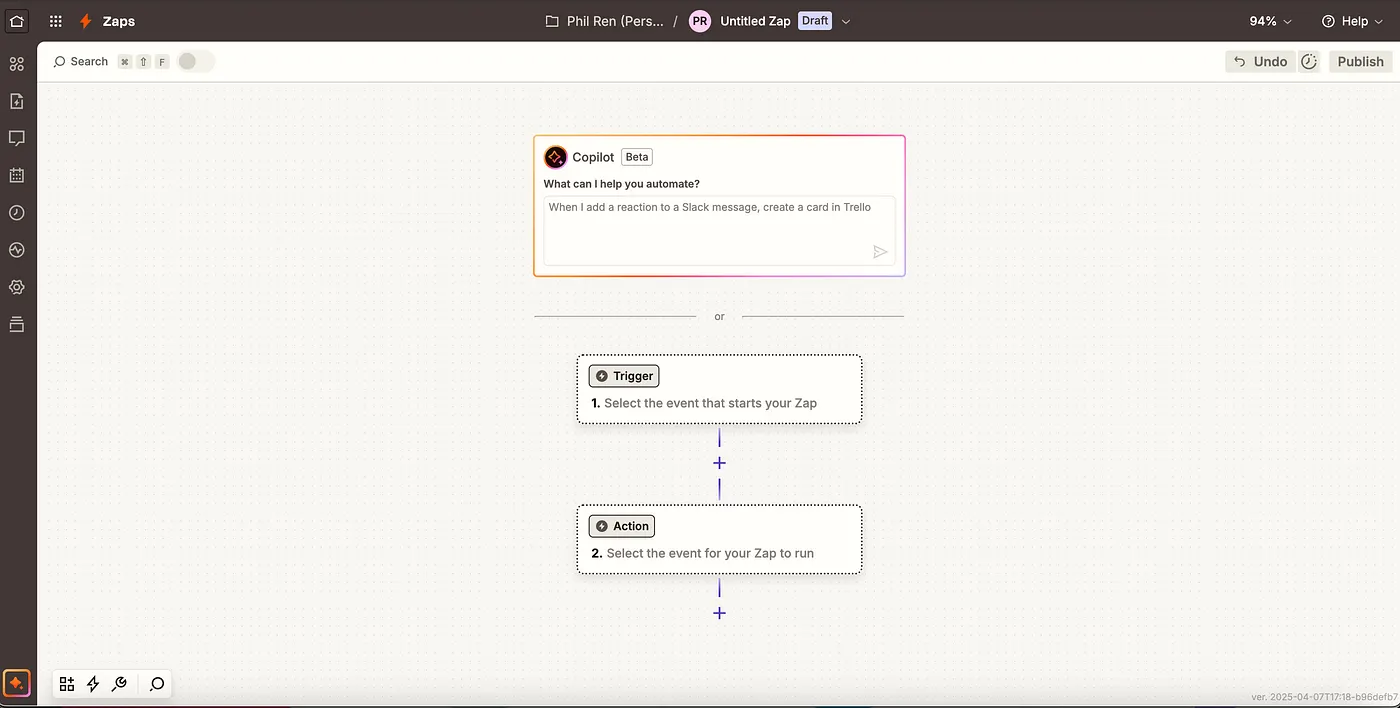

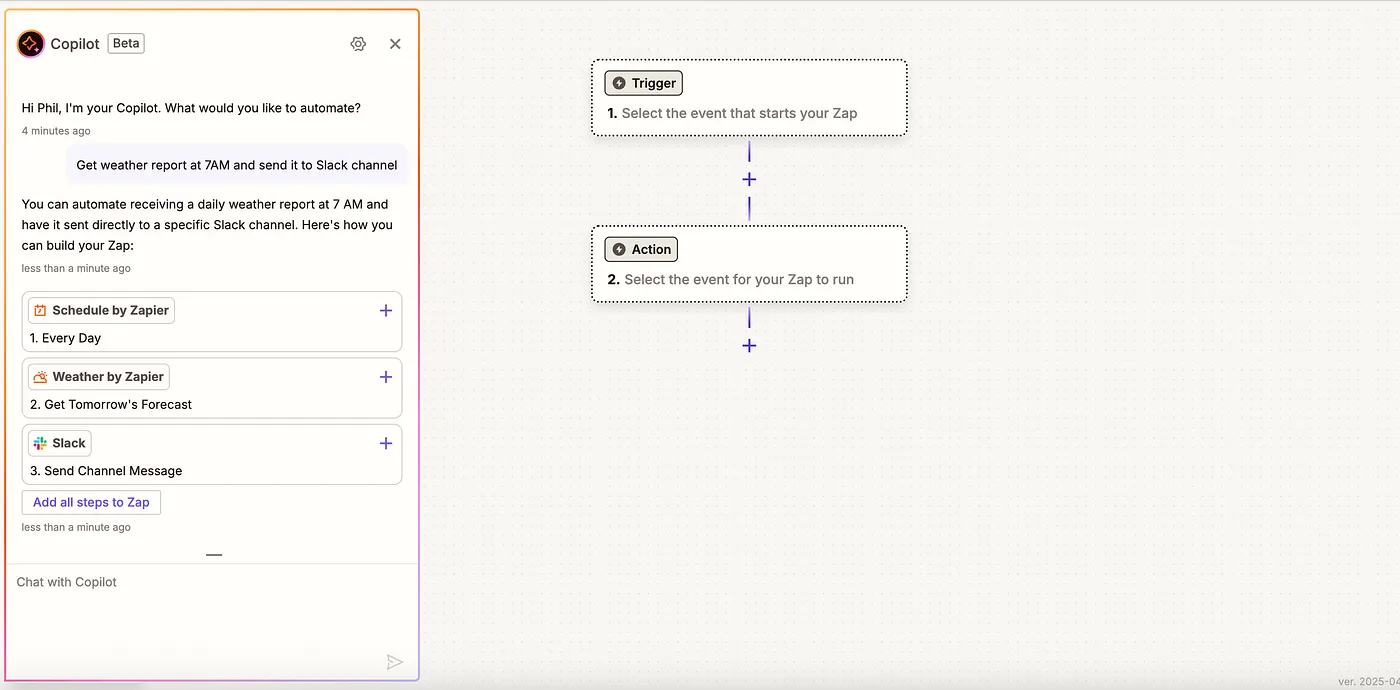

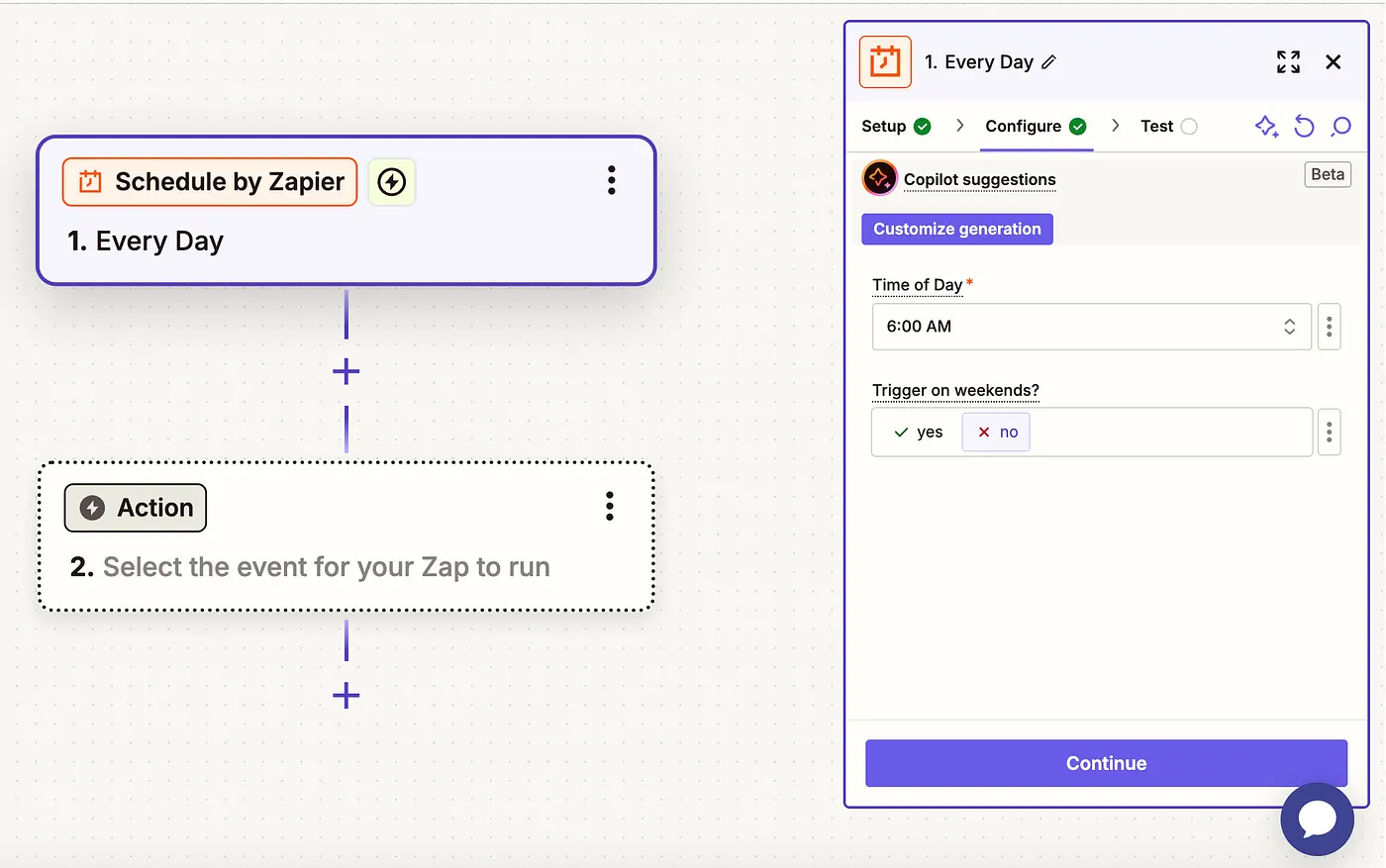

We now look at the second example. This example takes place in the field of enterprise software. Zapier is a platform that builds cross-application automation workflows for businesses. Recently, they launched Copilot, allowing users to describe the workflow they want to generate using natural language. For example, “Whenever a lead is added in Hubspot, synchronize it with Salesforce” or “At 7 AM every day, get the local weather forecast and send it to a specific channel on Slack.”

After the user completes the prompt (Instruct), Zapier does not directly create the complete workflow but instead provides a sequence of suggested trigger and action cards on the left side of the page (Visualize). Users can add the triggers and action nodes they think are correct to the workflow canvas on the right side by clicking the add sign (Edit). The right side canvas, with the AI capability integrated, doesn’t differ from the legacy canvas.

Once the nodes added to the canvas are activated, the user can use the AI button in the right node property dialog box to instruct the system to help configure the node parameters (Re-instruct). The baton continues to be passed until the user is completely satisfied with the configured workflow and finally submits it (Submit).

By using AI to make workflow configuration smarter, Zapier discards all exaggerated goals. Each step of the Copilot focuses on a small goal, and at each step, the user participates in the decision-making before submitting . This is the correct way for enterprise software to integrate AI capabilities. Through this paradigm, AI can be truly applied to practical production scenarios, rather than being just a gimmick for demonstrations.

To achieve this, Zapier had to do a lot of engineering work.

First, Zapier had to provide programming interfaces for all the components involved in building a workflow and convert them into a JSON statement that includes full semantic information. This is a necessary condition for enabling Function Calling, allowing the AI to understand the available actions.

Second, they needed to carefully plan the Agent combinations, ensuring that each Agent focuses on one specific goal and can communicate effectively with other Agents to pass tasks on to the next goal.

Finally, the AI-generated content must be able to directly communicate with the frontend, ensuring that the content generated by the instruction can be accurately rendered on the canvas. Once the rendering is completed, the user can directly take over to Edit or modify the Instruct.

With these engineering efforts, Zapier was able to implement a viable workflow orchestration Copilot. This approach is far more reliable than a one-click generation of a workflow.

The IVERS paradigm also allows application developers to decouple AI capabilities. Regardless of how the technologies in generative AI evolve, application software only needs to manage its own application development interfaces, configure prompts and tool definitions, and even if the large model changes, it won’t affect its code projects. In more complex scenarios, if the user needs to interact with Agents developed by third-party tools, the industry has already started attempts at standardization, and the MCP Server protocol is likely to become the standard in this field.

Most application software needs to rethink how to integrate with AI capabilities. By not abandoning their unique positioning, they have the opportunity to gain new energy in the AI wave. However, in fact, many applications are undergoing a “transformation”. Tools, platforms, and application suites are rushing to create intelligent agent orchestration tools, as if overnight everyone has become a native AI application. The market does not need so many Agent Builders but rather more and better applications that integrate AI capabilities. These transformation efforts require time and effort. No matter how much AI capability improves, when applied to a scenario, it requires software vendors to connect the dots and solve a large number of engineering details before offering practical and reliable solutions. Therefore, one of the main objectives of this article is to urge traditional software vendors to re-evaluate their AI strategy.

In a recent interview, Microsoft CEO Nadella made a very extreme statement. He believes that AI and intelligent agents will destroy all legacy software, especially enterprise software like Dynamics, which he believes is merely a database with a bunch of business logics. He thinks that in the end, the AI layer will not only replace the GUI layer of existing software but will also take over the business logics. I think he may be pretending to be self criticizing, considering Microsoft owns every aspects of AI and application businesses. First of all, I don’t believe the GUI has no unique value. It is an essential component of software technology and will persist for a long time. Even configuring an Agent workflow still relies on GUI now. Secondly, we should not confuse the vision of several decades from now with the shortcut to achieving it. Based on my experience in the enterprise software market, neither software nor AI creates miracles. There are only incremental efforts.